Щойно забрали наклад із друкарні, починаємо відправляти примірники. Замовляйте онлайн, або купуйте в книгарні Збірка за адресою вулиця Золотоворітська 2а.

Категорія: Без категорії

Третя Нога!

Третя Нога вже друкується і скоро вийде! Приходьте на презентацію до книгарні Збірка у п’ятницю 4 липня о 18:00. Вестимуть розмову Ліза Білецька, Філіп Оленик та Борис Філоненко.

Автор_ки третього випуску:

Олександр Стешенко

Сашко Протяг

Даша Суздалова

Кріс Краснопольська

Френкі Фрейр

Антон Полунін

Сергій Рафальський

Катя Лібкінд

сід

Анна Мєлікова

Катерина Алійник

Дарина Малюк

Олена Думашева

Ян Спектор

Оксана Брюховецька

Ольга Марусин

Назар Беницький

В’ячеслав Лисиця

На обкладинці використано роботу Катерини Алійник “Гнилий красень” (фото зробив Володимир Прилуцький).

Опен кол

другий випуск ноги ще гримів та котився долинами коли з далеких верхів зелено-голубих, чи то з крану будівельного, залунала пісня, така дивна й забута що ви скажете ВАУ:

!~ми оголошуємо опен кол на третій номер~ !

час є але його і небагато. шліть нам ваші драми, доки, фенфікшени, частини неопублікованих книг, підслухані розмови, шматки, шматочки, маленькі віньєтки, вкрадені щоденники ваших друзів, колекції реклам, чеків, і прикмет, та і просто розповіді всілякі, художньо-документальні. приймаємо також і кураторські рекомендації + знайдені тексти. з нашими смаками можна ознайомитись прочитавши журнал. мерщій пишіть! як ви вже знаєте, наш журнал рухається в гіперзвукових темпах. чекаємо на вас дуже.

дедлайн 1 жовтня

за текст передбачується гонорар

сторінка сайту ноги для авторів може стати в нагоді: https://kyivnoha.org/authors/

тексти надсилаються сюди: [email protected]

кіс,

Л

Друга Нога!

Ви не повірите, але за кілька тижнів виходить новий, другий, інший, наступний випуск журналу Нога. Тим небагатьом, хто за чотири роки забув, нагадаємо: Нога — це журнал художньої документалістики, тобто документальної літератури, яка написана або читається з художньою метою. Майже всі тексти що увійшли до нового випуску були написані до повномасштабного вторгнення рф. Ці документи дуже різних світів і поглядів дивним чином резонують коли збираються разом у червні 2024.

Ціна примірника за передзамовленням 300 гривень, а коли наклад буде готовий 350. Відправляти замовлення почнемо наприкінці червня.

На обкладинці використано візуальну роботу Каті Лібкінд. А що всередині?

Випуск починається з тексту Дарини Малюк. Вона розмірковує про бажані предмети, шанс отримати які було безповоротно втрачено.

Інеса Марґ описує вбивство і перетворення на їжу кози, що постарішала.

Назар Беницький згадує дитинство та інтернат. У його зошитах спогади чергуються з щоденниковими записами про спроби побудувати автономне життя на острові.

Альона Думашева продовжує розповідати про своє ув’язнення у рф. Її новий текст про життя жінок-увʼязнених у Володимирській колонії.

Антон Полунін у поетичному тексті заповідає нам одну цінну річ.

Ліза Білецька розповідає про своє знайомство з компанією, що надає людям похилого віку послуги “пожиттєвого утримання” в обмін на спадщину на квартиру.

Філіп Оленик переповідає історії нігерійців та українців нігерійського походження.

Текст Дарини Малюк, яким починається випуск, було написано у 2020-му році. У останньому тексті Дарина розповідає про своє життя у 2023-му.

April 16th by SASHA STESHENKO

Ukrainian army soldiers captains lieutenants paratroopers tankers navies a big thank you to all militaryservants men come back alive healthy you are our shields all soldiers please protect Kiev Sumy Lvov Kharkov Poltava Kherson snake island Zhitomir Lutsk Lugansk Donetsk Krivorog Ukrainian army soldiers captains lieutenants paratroopers tankers navies keep safe please keep safe our country don’t allow this scum dank brutes tell us how to live what to eat what to drink what clothes and shoes to wear how to feed and give ourselves drink that there are peaceful people here I beg plead implore Ukrainian army soldiers captains lieutenants paratroopers tankers navies please only protect our families wom en children veterans Ukrainian army soldiers captains lieutenants paratroopers nkers navies men militaryservants Ukrainian army soldiers captains lieutenant paratroopers tankers navies please come back alive healthy to your mothers and wives children save everyone the world Kiev Poland Germany Japan China Georgia Great Britain Amer ica France Azerbaijan Armenia Spain Portugal Ukrainian army soldiers captains lieutenants paratroopers tankers navies you’re our good sports like they sing in the song oh in the fields the red guelder volunteers you are our boys men militaryservants though I’m a Georgian my heart is Ukrainian a big thank you for everything you’re our volunteers you’re our protectors and brothers to our Georgio-Ukrainian country by blood our blood of all sorts Georgio-Ukrainian flows in our veins and we will never forget this day thank you our colleagues warriors of good th ank you that you gave us Georgians your Ukrainian shoulder to lean on in 2008 while this dank scum attacked in our beloved Abkhazia

16,04,2022 20:12

Saturday

Sasha Steshenko is a member of the art collective atelienormalno.

April 20th by ALEXEY SHMURAK

Some facts from my biography

=

Some facts from my geography:

————————–

I have never been to Mariupol’

I have never been to Bucha

I have never been to Gostomel’

I have never been to Irpen’

I have never been to Kramatorsk

I have never been to Volnovakha

I have never been to Kherson

I have never been to Melitopol’

————————–

I will never again be in Moscow

I will never again be in St. Petersburg

I will never again be in Nizhny Novgorod

I will never again be in Rostov-on-Don

I will never again be in Lipetsk

I will never again be in Vologda

I will never again be in Minsk

I will never again be in Grodno

————————–

I will never have been to Yekaterinburg

I will never have been Kazan’

I will never have been to Novosibirsk

I will never have been to Baikal

I will never have been to Gomel’

————————–

Some questions for my biography

=

Some questions for my geography:

————————–

Will I ever be in Simferopol’, where I have not been since 2004?

Will I ever be in Sevastopol’, where I have not been since 2011?

Will I ever be in Yevpatoriya, where I have not been since 2009?

Will I ever be in Donetsk, where I have not been since 2012?

March 30th by TASYA SHPIL

Today at the train station I met Zelensky’s teacher. That’s exactly how she introduced herself—first as Zelensky’s teacher, and only then as Alla. She is traveling back to Ukraine. She says, “Girls, one month max and you can come back home.” She says it with such confidence that it is impossible to counter her. But first Alla needs to make it to Wroclaw to visit her grandchildren.

The free direct connection to Poland has been closed for at least a week: you can get there either by regional trains and a bouquet of transfers, or for money. This is Europe’s hint that evacuation does not entail the possibility of making a step back, yet many Ukrainians want to be closer to home or to return home already.

My job today is to explain this convoluted route to those traveling to Poland. I deliver a speech to Alla that’s now drilled into my brain, about Frankfurt on the Oder, Rzepin, Warsaw, times, platforms, train numbers. The train from Frankfurt to Wroclaw isn’t regional, it requires a ticket. Alla understands this but is still determined to board this train for free. There are these types of people who will break any silly human rule in the name of a great cause, and they do it with a smile, and they get away with everything, and Alla is one of them. I know that nobody will be able to unseat her from this train, traveling to the flaming east. Alla does not need a ticket home. I show her the path to the platform and take off my orange volunteer jacket.

Three poems by ANTON POLUNIN

March 5th

heaven on their minds

war’s war and poetry

is war

while scotchtaping the window

in case of an explosion

so shards won’t cut any of us up

i sealed a trace of marta’s lips on the glass

marta loves

to press her face to the windows

though now

you can’t come near the windows

unless you’re taping them with scotch

so that during an explosion

the shards don’t cut anyone up

now marta’s kiss

is addressed to the world

– the friendly

that fights to the death

sits in the basement

stockpiles gas

and food

and body vests and everything

to meet the inevitable

– the hostile

that pelts us with deadly things

snoops around our forests leaving tracks

generally deprives us of everything but dignity

in an unusual way for me personally

– the neutral

that sends us its shitty love and support

this kiss of marta’s

has modest chances of being passed down

should we have descendants

as proof that in in this world

there’s a drop of love

or at least a trace of it

what if i die

asks jesus from the rock opera

my kids love rock operas

relax jesus

everything will be fine

just die

05.03.2022, Brovary

March 21st

so here we are blyad’

i’m an internally displaced person

a fucking

internally

displaced

suka person

my dear lovely

esteemed and highly esteemed

refugees

people who received

additional protection

and temporary protection

and also idp’s

i sincerely admire you

and wish you all the best but

to join your ranks

well that’s like i don’t know

to be a conductor

a space paratrooper

a merchandiser

honorable work and so on

but personally

fuck that

we left at seven

and creeped for a long while along the fields

black like chernozem

until night fell

also black

starless children

were bored first

then hyper

then pissed themselves

right in my lap

so we pulled over to a gas station

where there was no gas or coffee

or anything

but half a dozen cars that huddled

hoping against hope for something

also the navigator

constantly led us astray

maybe because

we originally

set out astray

and now I am here

where I do not want to be

my dear

incredible

wonderful

you can’t even imagine

how happy I am

to see you

but fuck staying here

in this jackoff

motherfucking safety

where it smells like children’s urine

and yesterday’s sandwiches

though of course

people live

and war isn’t forever

and rylsky too wrote love

love he wrote is worth it all

your pain

separations disgust misery

mad howling

madness or

mercy

and some other thing

i cannot recall

April 8th

you can appoint a poet

controller of beaten rabbit meat

chief of staff of territorial defense

deputy head of the

legal department

but a poet

if this is a real poet

always remains first and foremost

a killer

and poems

yes real poems

are written at least with the help

of an automatic rifle

this is called automatic writing

a protomodern/modern practice

of creating wasted texts

in the mouth of the bird of paradise

there is a place for dead warriors

who in the last

in the very last moment

did not fear death

even now on their faces

there’s this look

like wow

not scary

you can write the poet’s phone number

on a paperslip at the draft office

you can tell him

we’ll call you

and then not call him

and give his rifle

to some prose writer

or artist

a poet meanwhile

a real poet

will still write

that he cut out the enemies’ eyes

and drank them in a bloody mary

and cut out their hearts

or whatever they have instead

and watched as dogs gnawed the feet of the dead

and gnawed them too

and after the victory

he’ll become a theme park soldier

to eventually die of cirrhosis

like he dreamed at sixteen

in the throat of the bird of paradise

there’s a place for those who

in the last moment

realized that this is

in fact death

disappointment is read on every one

of their faces

the paradise bird pecks pecks

the paradise bird is occasionally sick

and instead of muscovy there’s hardened pitch

and over that pitch a sulfur mist

and here the fields cover poets’ corpses

sprouting factories and industrial plants

banners and flags, titles and lands

wonderful are thy works whats-your-face

wonderful are thy works

Elegy by VLADIMIR ZHBANKOV

Sometimes it happens moan or mute

The world rolls up into a chute

A great trombone a trumpet

No a French horn

And in this place of dark and brass

Where sound is bent to narrowness

The valve is pressed but in such fuss

The notes produced come out all wrong

And with poor timing

But who are you to arbitrate

And moreover to love to take

A run about exuding pep

But I will note that to forget

Or cover up at least a bit

Will years require

A lifetime easy one can spend

Although you won’t and in the end

Not everyone does get one

Alright alright I’ll write-rewrite

I tell you what I’ll take a bite

Your humor’s rude and out-of-date

The soldier’s coming down the place

He lights the rubble with his light

But thus reveals unto his sight

A bit of nothing

The rubble’s like a microcosm

Not “like”, it is a microcosm

A fractal, brick, bone upon bone,

And parts of bodies loosely strewn

And from on high comes the abyss

The one that we call bottomless

Ah well, that’s that then

Ashes and Snow by ALEXANDER MOZAR

Unfortunately, I have memories that I will probably never share, but let these notes, written from memory, remain with me. Here is the city of Bucha near Kyiv, under shelling.

A man draws circles across the sky with his finger, then furiously hammers the imaginary ground with his fists. This is how the deaf man shows me shelling that he is only able to see. Broken glass underfoot, abandoned things, the chaos of war. A man’s corpse by a shot-through car. About a week ago, people covered up the body with a blanket. Snow and ashes fall on his gray, tired face. The dead car still has unshot wheels.

Wheels

Our neighbors are taking off the wheels. My brother and I help roll them to the house. Wheels are needed to change out tires. When combat operations only just started, some unknown person punctured the tires on expensive cars. At first residents thought it was saboteurs, but later, an experienced person of uncompromising appearance informed us that this was probably the work of criminals. Broken windows and robbed car interiors corroborated this interpretation. The neighbors change out the wheels and prepare for evacuation.

Evacuation

Cars bunch together in columns and, under white ribbons and flags, move out of the city in nervous lurches. The sides of the cars read “People,” “Children.” Tired people look indifferently at those remaining in the city. The remaining, too, for the most part do not pay attention to the departing. Everyone has their own reality and their own tasks. By the houses there are fires, people making food, people laughing, listening to the news, helping each other, sharing medicine, food. People are living through another monotonous ashy day. The next day is declared the day of evacuation under the protection of the Red Cross.

Several thousand people have gathered near the city administration building. Many are in high spirits, even though a car with a “200” on its windshield is driving around in visible proximity. The car is collecting corpses from the streets. Here it is worth saying that the streets are not littered with dead bodies, but there are dead people. Children examine the military with sincere curiosity.

Children

Unexpectedly, a closed mail van stops near the filing refugees. The car is inscribed with “Children”. The driver, insistently, with a shout, declares that he will take only women with children. His humanitarian appeals are ignored by large, broad-shouldered men. Only a few women manage to get into the van. The driver, bewildered, waves his hand and gets into the car. The departing “children” are sent off with laughter and whistles: “Here are our defenders,” the women laugh, “children,” “orphans.” They leave. The remaining wait for the Red Cross several more hours.

We slowly drive through the city. Traces of battles, pogroms. Emptiness.

Beginning

On the street, a man playing the role of the intellectual drunkard, looking by turns at me and at the war, rhetorically remarks to the sounds of the cannonade: “Ah, but I am a purely civilian person, and I could shit myself.”

The unexpected, new reality has not yet become a fact. TikTokers on skateboards are making videos against the background of a destroyed military convoy. Communication with the outside world still works, and many feel that everything will soon end or even already has. Incredible rumors and optimistic plans for the future. To Bach’s partitas, through the window, we observe helicopter attacks on Gostomel airport. Then aviation and artillery. Flashes. Lights off.

Weekdays

Electricity, water, heating, everything has been turned off. Snow fell on the morning of March 1st. The temperature in the apartment falls: 15, 14, 13, 12… It’s cold and monotonous. People are cooking food on fires. Our bomb shelter is just a basement. The people of our house, neighbors, often meet for the first time by the fire. We are finally getting to know each other after living together for ten years. Very valuable are the meetings with people you know.

“You didn’t leave, Alexander Vladimirovich?” A neighbor greets me. I shake my head. “The people’s lot, and ours too,1” she concludes looking at the droning sky and goes about her business. A new social hierarchy has arisen very quickly within the group of people near the bomb shelter, and those who in the past, before the war, had more significant positions in society have remained on the sidelines. People of a different tactic have come forward, i.e. those who give orders, even silly ones. All of this is expected and natural. The ability to obey and command is now in demand. It calms people down. Everyone becomes a group that “absorbs” stress together. There is boiling water, food, night duty with an axe. Next to us is an abandoned bulldog cut with shrapnel. Everyone calls him Patron2.

Animals

The departing let their dogs and cats loose onto the streets. But in this house, in the apartments, animals are still locked up, we hear cats going crazy, left without food and water. We can’t help them. People are afraid of marauders, who break into places under the guise of saving animals.

Marauders

My brother and I go outside and notice strange, jovial agitation. Outside some of the houses, swollen-faced citizens have organized festivities. A little further on, we come across a man with bags full of beer and cider. Seeing me and my brother, the man is clearly frightened and begins to confusingly explain that “everything has already been snatched up, but you can look.” Understanding nothing, we move on until we stumble upon a looted beer stall. Then they started breaking down the shops. Later, the merchants themselves opened up the storerooms that had not yet been broken into.

The city’s food logistics are paralyzed. Emergency services, medicine, have remained inaccessible to us. Snow, broken glass, and sky soot.

After what was written

During the last days of my stay in the city, I did not take any pictures or videos. The war rolled in and became commonplace. A complete change in the informational space, in a broader sense than “the media.” The concepts of morality and mercy voluminously unfold. Everything changes, including one’s perception of people. Everyone adapts to constant stress in different ways here. Often, one reality disrupts into another. A girl who addressed even animals with the formal-you, now, under mortar explosions, cheerfully, enthusiastically talks about her niece. When the fire subsides, her face changes and she suddenly exhales hysterically with a cry, “Blyad’, when will this fucking hell be over.”

We are in Kyiv. Conversations with Volodya and Lisa Zhbankov, Polina Lavrova, Olga and Varya on abstract topics. In the morning, unexpected sun on the boulevards of an empty city.

February 24 – March 12, 2022

Bucha – Kyiv

1 Literally: As for the people, so for us. An ironic proverb.

2 Besides “boss,” Patron also means “ammunition round.” It is common to name animals after military effects during wartime. This time around, we have also seen Javelins and Bayraktars.

March 28th by DIMA KAZAKOV

Every day my Kyiv is getting better at shooting down missiles with antediluvian anti-aircraft defense systems, sometimes not even bothering to turn on the sirens. It appears the anti-aircrafters have now gotten it down so cold, there’ll just be a loud bang nearby and then a message in the local Telegram channel like, “all clear, it’s just our guys.” At any rate, Kyivans are by now well acquainted with the vocalizations of the machines protecting them.

Open for the second week in a row—and keeping the fighting spirit of Lvivska Square residents afloat—is the city’s best third-wave coffeeshop, which even serves two types of croissants: classic and almond. But you’re only allowed one per person; they sell out quickly, and everyone needs to get one: the national guard from the roadblock nearby, to go with his oat-milk latte; and the female volunteer with her arm in a cast; and the Dutch journalist dispassionately sipping his pour-over over the bangs of the anti-aircraft defense and the wails of the sirens. The barista, meanwhile, speaks Ukrainian to me, russian to the fighter and volunteer, and English to the journalist. Nobody is running for cover—it’s a sunny day, the coffee and croissants are too good, and the russians too ham-fisted.

This giant city, it seems, has converged, braced itself into a barbed sphere—an antitank hedgehog—projecting out:

antitank barriers and concrete roadblocks;

a television tower, which rusnyavoye high-precision weaponry managed to miss, concurrently burning several fucking people in Babiy Yar (including one russian citizen);

the monster building in Podil (but even this I forbid the fascists to touch with their dirty rockets; Kyivans will decide for themselves what to demolish and what to leave standing as a monument to tastelessness and corruption);

Shchekavytsa, with its Old Believer graveyard crosses and the green neon of Ukraine’s main mosque.

Everything is oozing mysticism. Like smoke from the fires in small nearby towns creeps onto Podil and Troyeshchina from the north. Of course, it’s always been here, all one-and-a-half-thousand-and-then-some years. In the place where this photo was taken there is at once a pagan shrine; the ruins of the Church of the Tithes, destroyed, along with tens of thousands of Kyivans, by the horde; and a memorial stone, upon which it states that Kyiv’s defense line passed through here during the last people’s war. It is here that my russian-speaking friend, the granddaughter of a Don Cossack enchantress, comes to sing-sling hexes for the occupants’ demise, in breakthrough Ukrainian. Everyone is speaking of kharakterniks1, witches, molfars2. Magical troops are operating in social networks, all Kyivans and Kyivesses are seeing prophetic dreams, obeying their intuitions, and literally physically feeling time’s flow towards our victory.

Everyone is ready to die. Another friend performed a ritual: when they bombed the outskirts across the woods from Irpin’, she left her house, lay down on the ground, and took death into herself, became them: earth and death. Many Kyivans did just this (maybe not to the letter), many Ukrainians from towns that are quiet and from those of which there is nothing left at all after a systematic annihilation. Everyone here has come to an agreement with death, taken it seriously, released themselves from it, and gotten back to their work. They volunteer, write code, burn russian tanks and the fools inside them.

Only the russians have not been taken seriously here. Everyone is laughing at them, at which they get all huffy, and all that’s small and pitiful in them creeps out. But how can we take seriously those who marauded Bucha, are about to fall into a cauldron3 (which, it is proposed, we should name “Bagatiy”4), to burn alive in their tin cans, but are calling their relatives to find out how much a looted graphics card costs, happy that “the little trip was reimbursed.”

Or those who, fleeing from moscow or st. petersburg (from what?) are whining in Armenia or Georgia that they haven’t created the necessary infrastructure for them, that they’re refusing to house them, in favor of real war refugees. As they themselves, in the meantime, cluster together, like on Brighton Beach, refusing to learn to say “thank you” and “good evening” in the local language. As they are shatteringly confused and crushed by their hypocritical guilt, their petty imperial—I forget the russian word—pyha5 (not to be confused with pihva6, though that’s what’s coming for them).

1 A part-sorcerer, part-warrior Cossack, found only in the Zaporozhian Sich. A soldier-shaman, spiritual leader, keeper of the traditions and secrets of Zaporozhian Cossack martial arts. Cossack Mamay was one example.

2 Hutsul healer, magician.

3 Kettle, pocket. Group of combat forces that have been isolated by opposing forces from their logistical base and other friendly forces.

4 “Rich”, orthography implying a russian accent. To read more about the class axis of the Bucha massacre, let this translator suggest a post by Mykhailo Bogachow.

5 pride

6 Literally: vagina. Figuratively: “they’re fucked”.

Two prayers by STAS TURINA

March 11th

Lord, look each enemy of ours in the eye

Lord, embrace each enemy of ours thoroughly

Lord, tell each enemy of ours what You consider necessary for him to hear

Archangel Michael, give each enemy of ours a blessing of fire and sword

Archangel Michael, give each of us Your unknowable shoulder to lean on

Archangel Michael, see from where our enemy grows

Sear the tail of the enemy’s patron and his face

Whoever inspires the enemy, let him remove his fingernail from our land

The known and the unknown, let him know Your, Archangel’s, everything

The bell will ring

Truth come true, guilt aggrieve

So I write mid-night for safety

March 26th

Lord, you gave me the chance and opportunity to return home today

Beyond the doors lies the garden

“Light moves from the house, Christ moves to the house,

Guardian angels, take care of me”

Here, Lord, You are near

Sounds of blasts open the heart

Lord, You have given us such strength, there is already enough for quarrels and arguments, thank you

Lord, teach us now how to argue well,

Teach people of good will to keep each other safe from hurtful words

Give eloquence to those who now so need it

Lord, protect us in the silence of the night

Archangels, bare your swords, give your banner, our enemy’s last chance to stop

Let people in danger pass through the danger: stand on the crocodile, with a most open hand turn away the lion and the hippopotamus

With fire and sword protect us, Lord!

Do not abandon us in this difficult hour

All that I have, I put at Your feet, Christ

With choirs I call to the heaven, like Sirin!

translated by Lisa Biletska

March 28th by STAS TURINA

A few more pages.

Our house is next to the forest. Behind the fence there’s the forest, a belt road, and then Irpin’.

Yesterday Katya and I worked in the garden (at first I misprinted and wrote “in hades”). Planted some things. Fed the neighbors’ dogs. I won’t tell you about my days in detail just yet, there are a million details, all of them interesting.

Even before (this “before” is now synonymous with “before the 24th”), the forest echoed back fear. Our street and the adjacent street are always deserted in the fall and winter. People drive cars here, few walk. Is this the kind of garden Bulgakov’s Master dreamt of? The shudderings of the house no longer scare me; as long as the windowpanes are intact and the sounds far off, we are safe. The screeching of gunfire spurts in the forest has become similar to a bird’s. We have our own woodpecker too; he doesn’t live in the garden but comes to visit. The trees are sick, and he has enough food. Spring is wild this year. The water near the house is frozen again. Hello! It’s March 28th! I call out to my relatives in Kazakhstan. Why to them, exactly? I don’t know. Maybe not to them.

Good deeds must be kept secret. And I tell everyone. Not so much about good deeds, but about the mechanisms of good. About God. When I talk to people about God, something changes in me. A small good deed is a big beginning. What can this be compared to? For example, to the size of a 5mg pill, to the size of a needle and thread. The action of a small deed is like the removal of a stone or leaves from the watercourse of a spring. Small unresolved deeds are rolling pins (splinters, in Russian) that get in the way of living through work, plans, and well, everything, in short.

The house is humming with shelling. It’s as if the underworld is breaking out. But in vain. Vain efforts.

In the morning I understood and told Katya: “I have found the path to victory.” It sounds silly and it’s making me smile too. Here is the path: find one useful activity each day. At least one. And do it. God, it all sounds so much like psychiatric rehabilitation. Like when grandma and grandpa made me work, in 2013, and then for five more years. Though really, at first, there was no work to do. They just wouldn’t let me do it. Because they found their jobs in the house, orchard, and garden on their own. And they were copyrighted, they didn’t want to share them. In the beginning—and all these five years were the beginning—I had to wash, sweep, just help. They didn’t let me do a job from A to Z. Soon after Katya and I started doing something full cycle in the village in our lean-to, my grandfather died. Now, these days, I look for jobs to do. So the day passes. Sometimes I fall asleep accidentally in the evening. Work makes for good sleep and a good appetite. There is strength enough for jokes and no time for anger. I quickly tell someone “goodbye,” and then go do something.

“Nature is dead.” That’s what Myroslav Yahoda once told me. The photo is a view from the windows of his studio. Myroslav. He is one of the people who taught me that life is not a joke. Though I did not fully learn this. I look out of the window, and there are trees and grasses that will not tell me anything like you will. And yet sometimes they say something, they speak Universe. Myroslav heard angelic choirs, he told me. I was asking him something about trees. What did he say to me that night? I was telling him about love, about a craftswoman who leaves no traces, I was elusive, concealed the name of my beloved.

“Cities are people,” a friend of mine told me once. Cities, cities… To see Ilya, Anton, Larysa, Sasha, Misha, Serhiy, Sasha, Yan, Zhanna, Valera, these days.

Conclusions disappear in pilgrimage, as the end disappears in the process of laying out a mandala of bread crumbs and pieces of porcelain. To write a text, to speak out loud. Who makes a mandala of someone else’s hair? : 12:00

To the sound of Irpen’s liberation we treated the orchard. It thundered in a new way now. Something about sex.

Working the orchard as a meaningless occupation first flowed from my own hands today, this practice was grafted onto me by grandfather Turina, on the streets they called his father Root. I seem to be of some rootful kin. Right now someone from this kin may be mobilized from Shakhtarsk or Debaltseve. I don’t know if they know anything about their great-grandfather. And I know little myself. He taught my father about life. Like my grandfather did me. A family tradition, it turns out. Anyways, I’m tired. The wind and air do away with any excess energy. I’ll eat some mayonnaise. I’m fat.

Yesterday they sent us humanitarian aid. Mood’s like the time when they sent us humanitarian aid in the 90s. Everything is so other-colored.

It seems to me that I will be able to kill a person, but this is not certain. : 20:37

First photo: view from Myroslav Yahoda’s studio

Second photo: our orchard

translated by Lisa Biletska

April 2nd by STAS TURINA

The day passes from a photograph of those shot in Bucha to a photograph of a trunk full of phones in Bucha

The day passes from ideas for a monument to Zhenya Golubentsev to the news that Vablya was liberated

The day passes from tasteless slept-on soup to sour cream

The day passes from the night shock of battering rain to a meeting postponed

The day passes in conversation with Petro Midyanka

The day passes in transition from the room of despair and resentment to the room where I am little with God

The day passes from searching for something and searching for my own voice

The day passes from threshold to threshold

The day passes from downloading a book to buying a book

The day passes from being lost in the supermarket to being lost near the bed

The day passes

The time for the funeral prayer draws near and arrives

Violetta says she heard the Angel of Death

and I believe her words

as if where there is no death, these days, there is no truth

translated by Lisa Biletska

March 29th by SASHA ANDRUSYK

one recent night i stayed up till two reading about nuclear escalation, a tactical nuclear strike, then woke up at seven, face to face with gek; he smiled and said: “do you know whose birthday it is today? yours! santa-frost will bring presents.”

i don’t remember what happened that day—after the nuclear detente—but when two weeks ago zhenya came to visit from nivky on her bicycle, she had to stay several nights. that arctic wind that was meant to turn tanks into 40-ton freezers grounded the bicyclists too. we went outside and reveled in how sharply it hit—a gift, a gift.

it’s hardest to wake from plot-heavy but peaceful dreams—the daily realization that nothing is over. the matinal creeping of sound: every day, a piece of the city is cut off. sometimes i look up the distance on a map—8-10 km from my house.

i know which russian army is sitting west of kyiv, in a marauding cauldron1, which is not a cauldron but a horseshoe, and we can’t just demolish it, we can only exhaust it with quick counterstrikes (will we take grandfather to irpin’ when everything is over? or should he not see what has become of it?)

i know that moshchun was liberated by a foreign battalion, i know the name of the anti-aircraft defense system that can shoot down a hypersonic “dagger” missile, i know the name of the general who is fighting against humanity in mariupol, i know that before this he fought against humanity in aleppo, i am waiting for his dog-death.

i know major prokopenko’s face well, with and without a gaiter. who will play him in the film about mariupol? orlando bloom? he just came to the moldovan border to meet ukrainian refugees.

the editor-in-chief of the bulvar newspaper delivers information to russia like a hypersonic dagger missile (get the fuck out of here!), and here is the information from major prokopenko: the situation is difficult but under control. no one is planning on giving up.

i know that for serezha, tenderness and metaphor are still possible, even on the night watch or in the morning, where these things end. this knowledge has illuminated one full day and illuminates minutes of others.

i hold onto the lives of those i know as if solipsism could be salvation, as if it is only those whom i know (have conceived of) that exist, and if they are alive and are not suffering, then everyone is alive,

as if in mariupol there was only daniil—and he has gotten out—and only major prokopenko, who is not planning on dying.

i think about how there is no enemy in existence whom we know better. we ourselves assembled its language three hundred years ago, we named it, we determined its ideological foundations. the great russian pomp is worth nothing here, the great russian impotence touches no one.

spring squalls, mine-studded bridges, kyiv split into halves—right bank and left bank. for several years i’ve lived in a house with the most beautiful garden outside my window. it stands on a sliding hillock, now placed on a powder keg. here, franya has teethed out 12 teeth in a month. for him, word has woven to object.

i can conceive none of this. and now the magnolias bloom.

—

1 (mil.) kettle, pocket. group of combat forces that have been isolated by opposing forces from their logistical base and other friendly forces.

March 28th by ANTON POLUNIN

yesterday I saw a ripped out dick

on a screenshot

dusted with dry earth

all alone in an open field

among human tatters

I saw a strip of face

a good few legs

and also how they were taking the scalp

off a man, still alive

this was in a rather brutal western

called scalps

an example of honest and informative naming

there was a scene

where they pierced a dude’s nipples

with hooks

then tied one end of a rope to these hooks

and the other to a horse

and let it run into the desert

then facebook deleted one of my texts

maybe

the word combination

fucking

moskali

die

bitches

did not seem militant enough

to facebook

in these harsh times

what to do

war is war

dick ripped off for one

text deleted for another

everyone keeps the score

of their individual losses

their own personal blacklist

for future reconstruction and revenge

right now on my list

there’s nothing of note

no wounds

not even any decent psychological trauma

though actually, today at the corner store, they ran out of vanilla doughnuts and I had to buy chocolate

nothing to be done about that, that’s war

the moskali can’t be envied at all

no sugar

no pads

president’s a dickhead

and the rest of them too

fragmented

moskal-meat

evenly blankets

fertile Ukrainian fields

still, the tribunal is soon

you can live in a clean cell

go to a toilet that isn’t outdoors

no bears

the Native Americans believed

that the souls of the deceased

continue to live in their hair

hence the theme with scalps

and burning books

the women of Carthage

donated their braids

to the armed forces

and I myself

haven’t cut my hair since the start of the war,

so that the soul doesn’t have to cram

itself into a lame undercut,

if, say, suddenly,

something I need gets ripped off

or facebook

deletes another text

March 26th by KATYA LIBKIND

I wake up every few hours amidst any kind of activity. Half-a-day barrages of catharses. Half a day of nothing. The thought does not let me alone that we are in some veteran’s recurrent nightmare, that they’ve slipped us a trauma that is not at all our own. Some dudes decided to create a reconstruction—with the same words, ideas, instruments, movements—a kind of game they’re using to displace what happened to them in WW2 and after. That the “great Russian nation” just needs to win the war again to forget that they’ve long been killed and repressed. Or maybe they feel that death is the only truth in their lives, and that’s why they so eagerly hurl their bodies at us, pressing to feel something a little real.

Time is arrested and deeply shocked.

I pray to materiality and to reality.

On the third day of war I felt fear creeping up to me, that kind of fear that, they say, makes your limbs go numb. I went out into the garden, lay down on the ground, and the earth went through me, through my tremor, and made me dead and invincible. I discovered that the only thing left from the fear now was its power. My body heats up and strobes like it’s getting ready to melt the world. I understand that the coerced freedom of humanity will begin with Ukraine. Everything that was, has gone to shit and will now grow again from this broken but very living and luminous center.

The butterfly in the video is Idea leuconoe. I bought her chrysalis and eagerly awaited the triumphant appearance of this sex machine, eagerly awaited her live beauty, and somehow attached too much importance to her arrival. A week before the war, she hatched; her belly was damaged, one wing was fully crumpled, the others she just couldn’t unfold. She tripped over her feet and tried to flap her soft wings for two more days. I fed her and weeped over her like I have not yet weeped over this war. My entire life coalesced in this unsymmetrical broken mandala. Everything that happened and everything that is possible will only be like this butterfly. Nothing more alive could have emerged for me. This is that center from which I now continue.

Напишіть для нас

Пишете в жанрі художньої документалістики або бажаєте почати? Напишіть в журнал Нога. Ми постійно шукаємо тексти для наступного випуску.

Наші умови і побажання до текстів на сайті журналу: https://kyivnoga.org/authors/.

Знаєте когось, хто пише і може зацікавитись? Перешліть їм, будь ласка, це посилання.

Назар відвідує Училище водного транспорту на Подолі

7 березня. Київ, Поділ. Назар звертається до чергової охоронниці на прохідній одного з корпусів Училища водного транспорту:

— А знаєте… Он та кутова будівля, ваш головний корпус, є у фільмі “Без году неделя”. Бачили такий фільм?

Охоронниця замислюється. Здається, не бачила.

— Там є такий кадр, коли Настя Філімонова випускається з училища і стоїть там у дворі. Це така світла сцена, у героїні багато сподівань, вона на відмінно закінчила училище і хоче стати капітаном річкового корабля. Вже потім вона з’ясовує, як важко для жінки робити кар’єру на флоті. Доводиться пробиватись, дуже важко працювати, щоб завоювати повагу і стати помічником капітана. Але зараз вона стоїть у дворі свого училища, а всі труднощі ще попереду.

Охоронниця посміхається. Здається, її тішить, що Назар знає такі деталі про місце, де вона працює. У відповідь вона розповідає нам про теперішнє хазяйство училища. Де які корпуси, де бібліотека, де вчаться, де здають в оренду. Показує кілька місць, які б мали нас зацікавити. На перилах сушиться червоний килим зі східними візерунками. Назар наближається, щоб сфотографуватись на його фоні. Виходить стривожений чоловік. Це його авто стоїть тут у дворі і він хвилюється за нього. Але нас цікавить тільки килим. Килим теж його, але він дозволяє Назару зніматись на його фоні.

Назар Беницький будує землянку на березі ріки Чорторий і працює вуличним музикантом на подільських вулицях. Початок його історії читайте в першому номері журналу “Нога”.

// Філіп Оленик

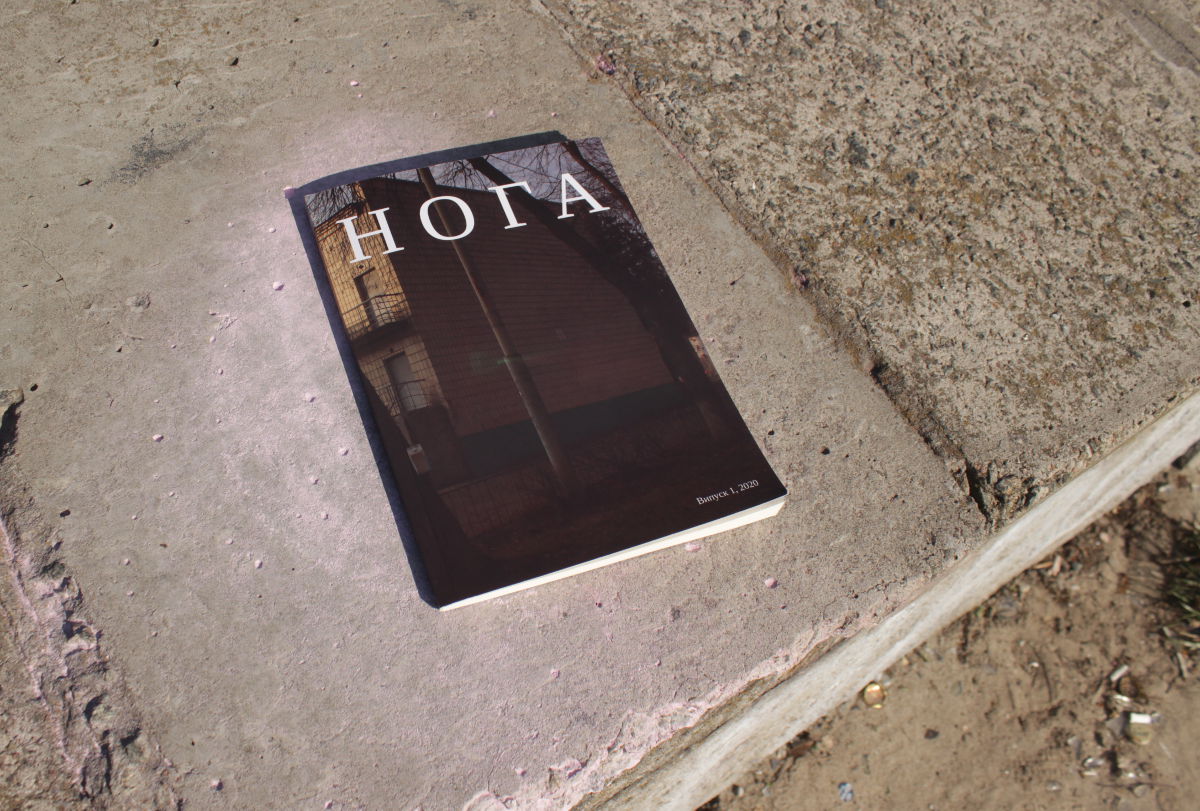

Перша Нога вийшла!

В цей буремний час наш перший випуск надрукований і чекає на ваші очі.

12 художньо-документальних текстів написаних в Україні наприкінці 2019 року. Тут: автобіографія людини, що живе на подільских вулицях, тюремні спогади студентки лінгвістичного університету, отруєне озеро та його пристосовані істоти, побоювання депутата, що лікарня це портал до аду, роздуми над мертвим тілом дельфіна, Google Borscht Results і дещо інше.

Автори першого випуску:

Назар Беницький

Оксана Брюховецька

Сашко Протяг

Олена Думашева

Олександр Авербух

Філіп Оленик

Володимир Жбанков

Катя Лібкінд

Ріке Феронія

Мішель Якобі

Антон Полунін

Ліза Білецька

Всередині журналу 104 сторінки. Картинок немає.

Ваш примірник за посиланням: https://kyivnoga.org/product/noga-1-2020-print/

Фото: Ліза Білецька

Дякуємо авторам

Дякуємо всім, хто надіслав нам свої тексти. Незабаром, до 1-го грудня, ми вирішуватимемо, які твори потрапляють до першого номера. Намагатимемося відповісти усім хто нам написав.

Тим часом, пишіть нам: [email protected]

Привіт, Нога

Ми задумали щоквартальний журнал. Він називається “Нога”.

Для першого номера шукаємо тексти в жанрі художньої документалістики (англ. Literary Nonfiction). Твори цього жанру базуються на реальних подіях, але не обов’язково мають на меті об’єктивно інформувати (як репортаж), навчати (як популярна документалістика) або висловлювати думку (як есе). Таким чином, жанр художньої документалістики знімає з тексту вимоги властиві іншим жанрам: текст не повинен бути ні об’єктивним, ні корисним, ні вигаданим.

Особливу цінність для нас становлять тексти, які документують активний та свіжий авторський досвід. Автор виходить в експедицію, взаємодіє, реагує та створює реакції, документує. Одна з переваг жанру полягає в тому, що робота в ньому не відбирає від “реального життя”, а стимулює його і збагачує.

Нас цікавлять, наприклад, такі теми: праця в робітничих немодних професіях; взаємодія з природою, у тому числі антропогенною; самотність, соціальне життя та дружба; громади й клуби. Цей перелік наводимо просто для прикладу: насправді, ми хочемо почути, що цікавить вас.

Але ми не стоїмо над ідеологією. Навряд чи нас зацікавлять тексти, які виражають упередження або зверхність до великих груп: національностей, гендерів, орієнтацій, соціальних класів, вікових груп. Кращий, на нашу думку, текст передає досвід і персонажів індивідуально та конкретно, без зайвих узагальнень.

Приймаємо роботи, які раніше не публікувались (в тому числі в соціальних медіа).

Мови: українська, російська, суржик, англійська.

Орієнтовний об’єм: від 5 2.5 до 30 тисяч символів. (Оновлення від 12.10.2019. Ми подумали і вирішили знизити мінімальну довжину тексту з 5 до 2.5 тисяч символів.)

За прийняті до публікації тексти передбачено гонорар 1000грн.

Матеріали для першого номера ми шукаємо до 15 листопада 2019-го.

Запитання, коментарі та ідеї текстів надсилайте за адресою: [email protected]

А ще підпишіться на нашу розсилку і будьте в курсі всіх справ.

Про нас:

Філіп Оленик – Дилетант, читач модерністської літератури 20-го століття. Експериментує в жанрі художньої документалістики в http://tinyletter.com/philya.

Лиза Билецкая – Редактор, переводчик, читатель. Пишет художественную документалистику: http://tinyletter.com/lisabiletska.